From ESS News

The basic structure of Na-ion batteries closely resembles that of Li-ion batteries, consisting of positive and negative electrodes, an electrolyte, and a separator. Round-trip efficiencies are similar to Li-ion at 90-plus percentages, but sodium’s larger particle size results in Na-ion batteries being bulkier and heavier.

Hithium’s one-hour battery energy storage system (BESS) was the latest product anouncement featuring a 162 Ah Na-ion cell, which the company says has a lifespan of 20,000 cycles. The product was launched last year at the RE+ exhibition in the United States and is positioned to address sudden load spikes in data centers while offering a longer lifespan.

Even if that claim proves true, a critical concern remains: Hithium did not disclose the data needed to assess power density, and Na-ion inherently has lower power density than Li-ion – an important disadvantage for the intended application of ensuring power quality, though not an absolute impediment.

Earlier in 2025, CATL launched its Naxtra Na-ion cell targeting the electric vehicle (EV) market, with a gravimetric energy density of 175 Wh/kg – very close to average lithium iron phosphate (LFP) – and a charge rate at 5 C. HiNa launched a similar product with 165 Wh/kg energy density. However, the most advanced LFP batteries achieve as high as 205 Wh/kg and charge at 12 C. This means that even at their new parameters, Na-ion will need to be relatively cheaper than average LFP and substantially cheaper than cutting-edge LFP to break through the niche status.

Challenges ahead

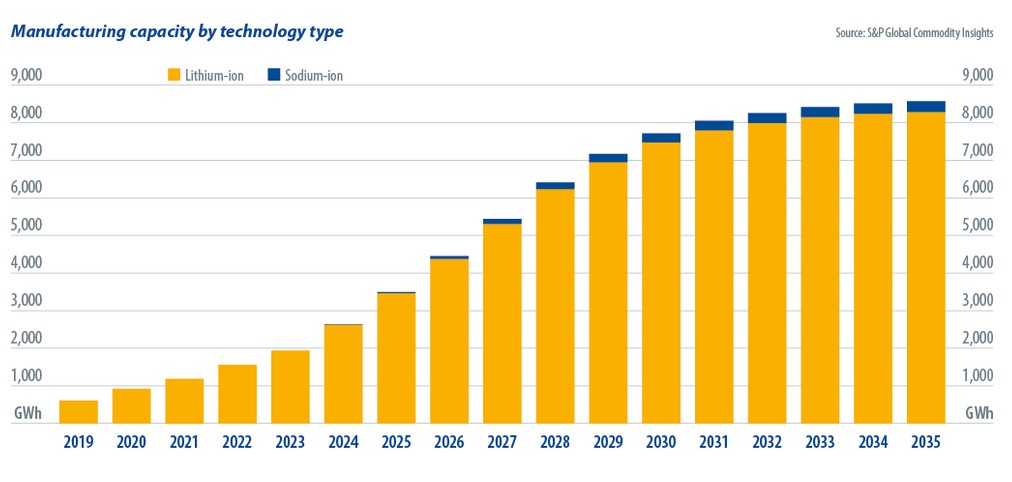

This is still far from being the case. The lack of scale significantly harms Na-ion’s manufacturing cost, which is estimated to be at least 30% higher than Li-ion at the moment, despite the potential to cost less in the future due to the use of cheaper raw materials. Sodium carbonate used in Na-ion batteries is far less expensive than lithium carbonate. The first is priced in the hundreds of dollars per metric ton, while the latter is in the thousands. Other materials employed, such as aluminum for current collectors instead of copper, are also more affordable. Even so, achieving cost competitiveness will require large investments and scaling of production, which is not supported by existing demand.

To continue reading, please visit our ESS News website.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own, and do not necessarily reflect those held by pv magazine.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.