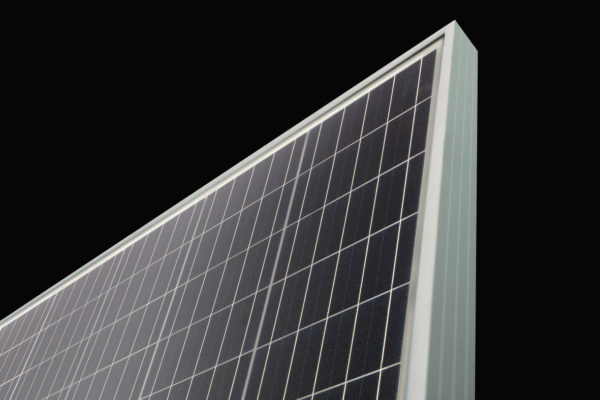

It’s not a new debate by any means. Glass-glass panels have been around for decades, and while glass-backsheet has historically represented the larger share of modules on the market, the strength and durability of materials for this component has also caused plenty of problems for the industry over the years.

The new wave of bifacial technology on today’s market brings further questions. Bifacial modules have so far mainly utilized a glass-glass (GG) setup – probably due to the lack of any other option. But now backsheet makers are catching up, with transparent polymer materials becoming available and the first glass-transparent backsheet modules appearing on the market in 2019.

“You can do glass-glass very well, and you can do glass-backsheet very well. It’s not a matter of one is good, one is bad. There are processes and materials available and you really have to look into the detail.” This statement, from TÜV Rheinland’s Jörg Althaus, sums up much of the discussion about glass-glass modules and installations at pv magazine’s Quality Roundtable event, held alongside The smarter E exhibition and conference in Munich in May.

The discussion revealed advantages and potential pitfalls at various stages for both technologies. And while the panelists broadly agreed that there is a lack of sufficient data for glass-glass installations to draw firm conclusions, issues and trends are emerging to provide the industry with lessons learned and best practice at every stage, from the sourcing of materials, to installation, through to operations and end-of-life management.

Testing, testing

Results from DuPont’s Global Field Survey, presented to the roundtable by Lucie Garreau-Iles, technical manager for EMEA at DuPont Photovoltaics, found that in a sample of six installations featuring glass-glass modules – around 12 MW in total – 13% of glass-glass panels surveyed displayed some type of defect, rising to 35% for installations more than four years old.

Common faults with GG modules identified in DuPont’s field survey included glass bending and breaking, delamination and corrosion. “When we compare glass-glass with glass-backsheet, there are some differences. We see more breakage in transportation and installation, but also in operation,” Garreau-Iles told the panel in Munich. “Glass is not a crystalline material, it will move and it may bend in the field. It depends on the type and quality of the glass. So how do you test for that?”

That new testing standards specific to glass-glass, as well as more data from the growing number of installations in the field, are needed to better understand how glass will behave as the rear side of a module quickly emerged as a key point.

Winfried Wahl, head of product management and chief engineer at Longi Solar Technologie GmbH, used choice of encapsulant material as an example.

“For glass-glass, you can’t use the same type of encapsulant as glass-backsheet. If you use the wrong encapsulant material, it’s the same as if you use, let’s say, a low-quality backsheet,” he explained.

“Manufacturers are in charge to really test the material combination, to do long-term testing before they roll a product out.”

Jonathan Govaerts of Belgium-based research institute Imec also noted the importance of testing both sides of a glass-glass module. That fits in with the broader debate over how to test and characterize bifacial modules. Imec conducted a study on potential induced degradation (PID) in glass-glass modules, and found that as well as a shunting effect on the front side, a polarization effect on the rear side can also exacerbate degradation. So in glass-glass, and particularly in bifacial modules, testing for PID needs to be conducted on both sides of the module. Current testing standards from the International Electrotechnical Commission don’t specifically call for this, but TÜV Rheinland’s Althaus told the audience that any laboratory called on to conduct this type of test would look at both sides.

Potential weakness

One question from the audience revealed a potential advantage for glass-glass modules, in terms of protection from cell cracking. Andrew Gabor, CTO at testing equipment manufacturer Brightspot Automation, told the audience that results from the company’s mechanical load tester show that in GG modules, no matter which side you press on the module, cells are never put under tensile stress, and microcracks never propagate into larger cracks.

Wahl agreed with this, adding that Longi’s results show GG modules perform slightly better in damp heat and other durability tests, since there is little or no moisture ingress. DuPont’s Garreau-Iles, however, sees this as further evidence of a need for glass-glass specific testing standards.

“We have found that you can’t test a glass-glass panel in the same way that you test glass-backsheet,” she explained. “When you test a glass-backsheet module, of course you should do UV, humidity and temperature tests, because that’s a potential inherent weakness. When you look at glass-glass you have the same potential issues, but glass is brittle and it breaks. That’s another potential inherent weakness.”

Image: JinkoSolar

Frameless modules

In earlier years, glass-glass was touted as allowing manufacturers to ditch the frame – one of the most expensive module components after the cell – which would cut costs significantly. However, this argument holds little weight with today’s experts, thanks to the many problems seen in the transportation and installation of frameless modules.

“I would never in my life ship frameless glass-glass modules,” said Wahl. “What you save on material you have to add to the packaging. That is a zero gain.”

For frameless glass-glass modules, additional spacers and protective layers are needed in the packaging to protect the junction box and prevent the glass from cracking in transit. And when it comes to installation, the weakness of glass compared to steel or aluminum frames adds complications and therefore cost, when it comes to clamping the module to a tracker or racking system.

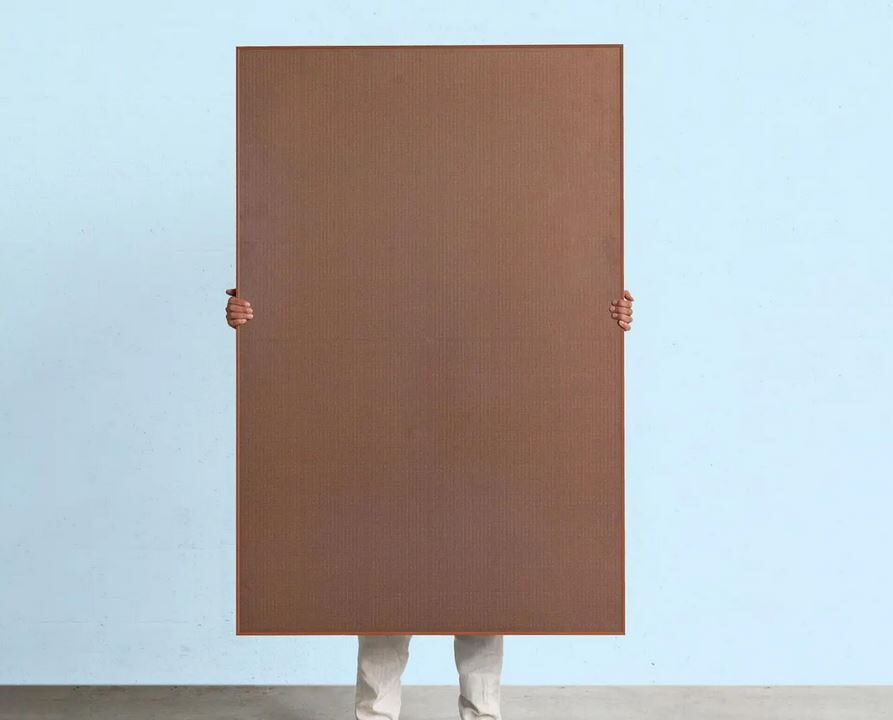

With the loss of savings from eliminating the frame, the advantage of glass-glass is less clear. “That is the reason we wanted to develop a solution with transparent foil, because in the end a frame is needed,” commented Andrea Viaro, head of technical service for Europe at JinkoSolar. “If you compare the price of framed bifacial modules, glass-glass versus glass-transparent backsheet, it’s truly cheaper.”

Testing has shown, however, that the additional toughness and protection against moisture ingress afforded by replacing backsheet with glass does offer extra durability, particularly in harsh installation environments. Earlier this year, JinkoSolar launched its Swan module, the first bifacial glass-transparent backsheet product on the market. And when the discussion turns to applying testing standards to this technology, Viaro is certain that Jinko’s latest offering can meet the challenges brought by conditions in the field.

“We offer the same 30-year warranty on both glass-glass and glass-backsheet,” he told the panel. “It really depends on the quality and durability of the material used as rear foil and encapsulant. We don’t use a normal EVA, and with the special tedlar-based backsheet, that’s a combination that allows us to offer 30 years warranty.”

With its transparent backsheet module, JinkoSolar has been able to achieve double the IEC standards in testing. Viaro also notes, however, that with glass-glass technology, they have been able to go even further and achieve triple the standards for certification. Outside of the roundtable discussion, JinkoSolar’s VP for global sales and marketing, Gener Miao, told pv magazine that while the company believes its glass-transparent backsheet product is the best option in most situations, there are still installations in which glass-glass will shine.

“In most cases transparent backsheet generates a better LCOE. But there are certain circumstances, floating solar installations for example, which naturally prefer a glass-glass product.”

In the end, both technologies can add up to good quality modules that meet requirements in the field for 30 years or more. Key to both is ensuring that all materials are properly tested before going into production, and that testing procedures accurately simulate conditions the module will be up against once installed.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.