It is a familiar reality in the market: the best product does not always prevail. Often, the cheapest option wins. No matter how advanced a development may be or how well thought out the concept is, a product has little chance of long-term success if it is too expensive or too complex to operate. That said, the lowest-priced product does not automatically dominate either. In solar technology, the balance between price, quality, and ease of use determines whether a product becomes a bestseller. Photovoltaic systems are designed and installed for operating lifetimes of more than 20 years.

From this perspective, manufacturers should equip solar modules with higher-quality materials and thicker glass, while inverters and batteries should use more durable electronic components. However, the sustained decline in market prices has created intense pressure that limits product quality. Costs are cut, and optimizations are applied at every stage to make products cheaper and lighter. Increasingly, more units are packed into a single container to reduce shipping costs. In many cases, it is only after years of operation that it becomes clear whether products live up to their promises or whether compromises have gone too far.

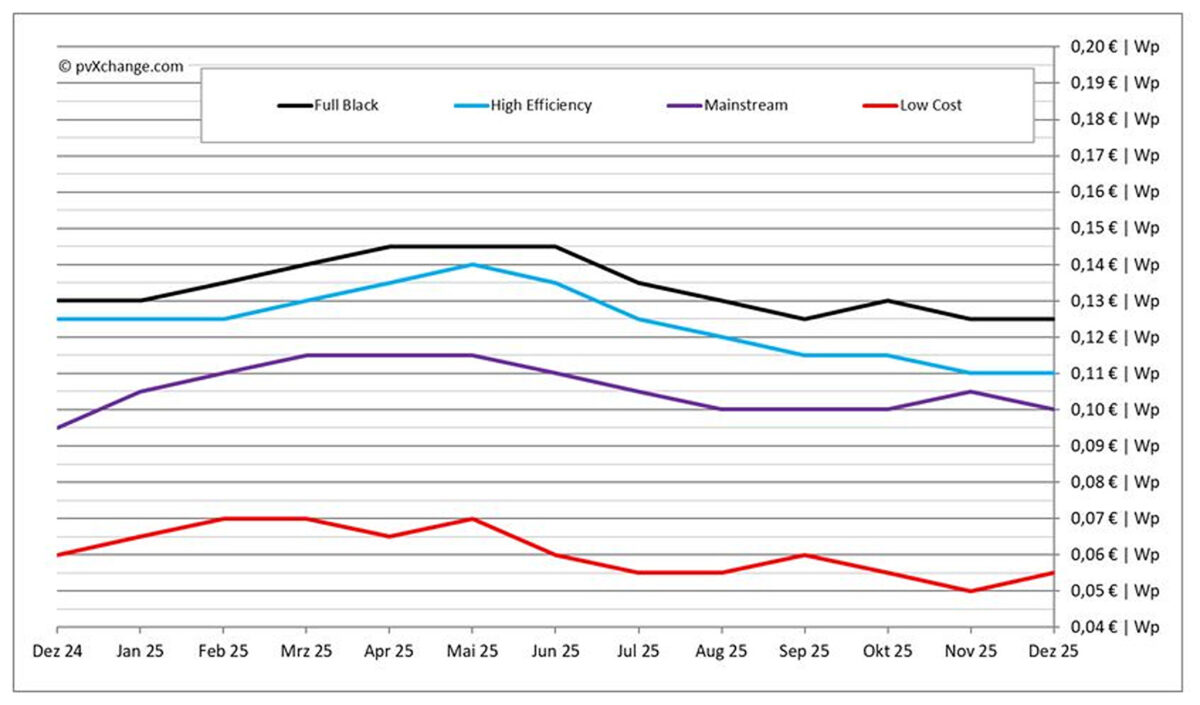

Module prices showed little movement toward the end of the year, suggesting the market may have reached a level where further reductions are difficult. Isolated deviations from the downward trend largely result from urgent sales or inventory clearances and do not indicate a structural shift. Given the substantial losses Asian manufacturers have absorbed for years, many expect an eventual upward price correction. The timing and mechanisms remain unclear. Higher module prices could enable manufacturers to improve quality again, but no major supplier is willing to move first. Large Chinese producers, in particular, fear losing hard-won market share.

Only diversified conglomerates that are not solely dependent on the solar sector, or smaller niche suppliers serving defined customer bases, can afford to price products above the general market level reflected in industry indices. The failures of Meyer Burger and SunPower, among others, demonstrate how difficult it is to sustain module manufacturing at scale when production costs are not aligned with prevailing market prices. This reality underscores a recurring challenge for system planners and buyers: an abundance of products, but too few reliable choices.

Experience shows that a conservative approach to selecting components and system concepts is often advisable. While innovation in the solar sector is essential and frequently drives major advances in power generation, it also carries significant risk. For capital-intensive, long-lived assets such as power plants, component failures after only a few years—or the disappearance of manufacturers and guarantors just as problems emerge—can have severe consequences.

There is no shortage of cautionary examples. One prominent case is the brief rise of so-called solar-grade, or metallurgical-grade, silicon in the early 2010s. At the time, strong growth in renewable energy created a shortage of polysilicon byproducts from semiconductor manufacturing. In response, researchers developed less pure silicon using simpler and cheaper production processes. In the era of polycrystalline modules, with typical efficiencies around 15 percent, these lower-performance products appeared commercially viable at the right price point.

In practice, however, modules made with these cells, marketed by Canadian Solar as “E modules,” degraded far more quickly than conventional products. Energy yields fell well below expectations, forcing manufacturers to replace modules after only a few months of operation. The episode ultimately led to significant losses and a rapid end to the trend.

Some of the most recent examples of ambitious but market-incompatible product developments can be found in the energy storage sector. One case is the year-round residential hydrogen storage system Picea, developed by the now-bankrupt company HPS. In this system, surplus solar energy is converted into hydrogen via an electrolyzer and stored in pressurized gas cylinders outside the home. When solar generation is insufficient, the hydrogen is reconverted into electricity and heat using a fuel cell. While technically sophisticated, the system is disproportionately expensive, limiting its appeal to a small group of self-sufficiency enthusiasts with significant purchasing power. By contrast, electrochemical storage systems are considerably more economical and, when properly scaled, can also enable near-complete energy independence.

Another example from unconventional storage technologies is residential-scale redox flow batteries. At utility scale, redox flow systems are a proven and cost-effective solution. Prolux Solutions, however, attempted to adapt the technology for use in single-family homes. In practice, challenges associated with circulating liquid electrolytes appear to have been underestimated, leading to leaks within a few months of operation. The high maintenance costs anticipated for a large number of small installations ultimately prompted the company to announce that, by the end of 2025, the limited number of deployed systems would be withdrawn or replaced with established lithium iron phosphate (LFP) technology.

In some cases, multiple development cycles are required before a concept reaches sufficient maturity or market conditions evolve to make it viable. Hybrid collectors—which combine photovoltaic and solar thermal generation—provide a clear example. From a physical perspective, the concept presents an inherent contradiction: excess heat reduces electrical output, necessitating continuous heat removal, yet doing so often leaves insufficient thermal energy for efficient heating applications. Over the past two decades, this principle has been revisited repeatedly, spawning numerous venture-backed companies, all of which ultimately failed. The breakthrough came when developers abandoned costly rear-side insulation and instead paired the collectors with heat pumps capable of utilizing low-temperature heat.

One useful indicator that a new technology may gain lasting traction is the presence of multiple companies pursuing similar approaches and bringing them to market. When several startups with comparable solutions succeed in attracting international investors, it suggests a development with genuine long-term potential. Once such products achieve meaningful market penetration, they warrant closer attention. At that stage, the risk of failure is significantly reduced—at least until the next disruptive technology emerges.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own, and do not necessarily reflect those held by pv magazine.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.