Delhi stands at a critical juncture where India’s ambitious climate commitments collide with persistent pollution crisis. The national capital, designated the world’s most polluted city, recorded its worst air quality in three years during October 2025, with the Air Quality Index frequently exceeding 400. This crisis reveals a vast gap between India’s climate promises and ground-level implementation.

India’s commitments are undeniably ambitious: 500 GW of non-fossil electricity capacity by 2030, 50 percent renewable energy by 2030, 45 percent emissions intensity reduction from 2005 levels, and net-zero by 2070. Yet Delhi’s pollution demonstrates that these macroeconomic energy targets are insufficient without corresponding transformation in mobility, urban systems, and enforcement.

The Transportation Trap

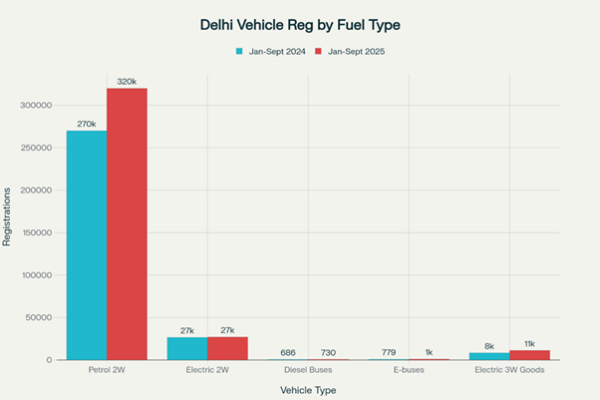

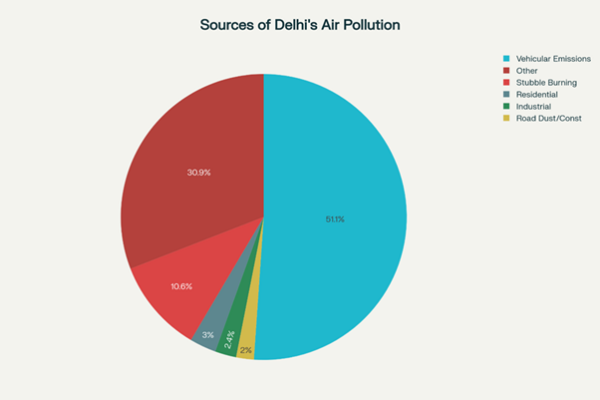

Delhi’s vehicle registration data exposes the first critical gap. From January to September 2025, the city registered 320,000 petrol two-wheelers compared to 27,028 electric two-wheelers—a 12:1 ratio. Vehicular emissions account for 51.1 percent of Delhi’s pollution, representing the single largest local source.

The problem is not insufficient emissions technology but explosive motorization overwhelming technological gains. An estimated 1.1 million vehicles enter and exit Delhi daily, creating a vicious cycle where congestion intensifies emissions and extends commute times, generating greater demand for personal vehicles.

Passenger e-auto registrations dropped to zero in 2025 after 1,198 in 2024. The implementation gap is stark: spare parts for electric auto-rickshaws cost over ₹1 lakh and are available only through manufacturers, whereas CNG maintenance remains affordable through established networks.

CNG vehicles present a paradox: substantially cleaner than petrol or diesel, yet representing a “climate trap” that addresses immediate pollution without enabling deeper decarbonization. With over 6,200 CNG stations nationwide creating locked-in infrastructure, and upfront costs 50 percent cheaper than EVs with five-minute refueling versus hours for EV charging, they remain rational choices for price-sensitive consumers.

Delhi’s EV charging infrastructure shows progress yet fundamental barriers persist. The city achieved 30 times growth in public charging stations within two years with innovative public-private partnerships and ₹2 per unit tariffs—among the world’s lowest. Yet charging remains slow: fast-charging delivers only 30-60 minutes of range per hour, compared to five minutes for CNG. For commercial operators, this productivity loss proves unacceptable.

Additionally, many Delhi residents lack private parking; significant apartment dwellers cannot charge at home. The residential sector mirrors this challenge: despite Solar Policy 2023 targeting 750 MW from rooftop installations by 2027, Delhi achieved only 302.1 MW—a 40 percent completion rate. The same coordination problems constraining EV adoption limit rooftop solar deployment.

Source- EnviroCatalysts Vahan Data

The Energy Transition Gap

India’s renewable sector achieved remarkable progress, reaching 203.18 GW by October 2024, the world’s fourth-largest capacity, with solar growing from 2.82 GW in 2014 to 123.13 GW. India achieved its 50 percent non-fossil fuel capacity target five years ahead of schedule in 2024.

However, non-fossil generation share remains stagnant at approximately 25 percent, revealing renewable energy’s fundamental challenge: intermittency. Coal-fired thermal power continues providing 70 percent of electricity generation, with the government explicitly maintaining coal plants before 2030.

Transmission infrastructure has become a critical bottleneck. To integrate 500 GW of renewable capacity by 2030, India requires 50,890 circuit kilometers of interstate transmission lines. Current progress proves substantially slower than required. On August 11, 2022, India lost 6 GW of renewable electricity due to grid constraints.

Approximately 40-45 GW of renewable capacity awaits signed power purchase agreements, reflecting transmission constraints rather than demand deficiency. Only 16 percent year-on-year growth in installed capacity has been achieved—insufficient for 2030 targets.

Delhi epitomizes these challenges with only 9 percent renewables in its power mix and 12 percent achievement of December 2022 targets. The city needs 24 percent annual capacity increase over three years to meet rooftop solar targets, yet peak power demand is growing due to increased air conditioning driven by rising temperatures.

The Battery Recycling Gap

India faces a critical battery recycling infrastructure gap threatening the clean energy transition. Formal recycling accounts for less than 5 percent of battery waste, while 90 percent is processed informally through hazardous methods. India’s Extended Producer Responsibility floor prices are too low to make formal recycling commercially viable, creating perverse incentives where informal recyclers undercut formal operations.

Without domestic battery recycling capacity, India’s renewable expansion depends on imported critical minerals from conflict-affected regions, externalizing environmental and social costs. For Delhi’s EV transition, this absence eliminates a critical incentive: low total cost of ownership through battery recycling value recovery.

Local Emissions, Not Just Stubble Burning

Recent 2025 studies found that crop residue burning contributes approximately 10.6 percent to Delhi’s annual PM2.5, with seasonal peaks reaching 35 percent during October-November. PM2.5 remained fairly stable from 2015 to 2023 despite stubble-burning incidents declining over 50 percent, suggesting local sources now dominate pollution. Three thermal power plants within 300 kilometers of Delhi emit 281 kilotonnes of SO2 annually; flue gas desulfurization could reduce this by 67 percent, yet only two of twelve major thermal plants installed this technology despite deadlines since 2015.

The Implementation Bottleneck

Delhi’s pollution crisis persists despite existing policy frameworks, revealing fundamental bottlenecks: coordination failures across agencies, financial structuring challenges, incumbent system inertia, scale-speed mismatches, and behavioral lock-in. Renewable targets cannot be achieved through technology alone; implementation requires addressing these structural obstacles.

Conclusion

India’s renewable capacity target represents necessary but sufficient progress toward climate stabilization. Delhi’s pollution demonstrates that energy supply-side transformation alone cannot deliver intended outcomes. Transport emissions, industrial activity, and residential heating must undergo equal transformation. The gap between climate talk and climate action reflects not insufficient ambition or technology but structural implementation challenges. Closing this gap requires shifting focus from ambitious targets to systematically addressing the bottlenecks that prevent targets from translating into outcomes.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own, and do not necessarily reflect those held by pv magazine.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.