pv magazine: What is SWAP, and how do your partners in this initiative support you?

Ankit Kapasi: The Solar Waste Action Plan (SWAP) Pilot, funded by the Netherlands-based Signify Foundation and Doen Foundation, aims to develop solutions for better management of end-of-life solar-based product waste, with a specific focus on PV modules.

During 2018, Signify Foundation, along with consulting firm Sofies, initiated the SWAP pilot’s first phase. During this phase, the SWAP team identified the different stakeholders that could contribute to developing the infrastructure/eco-system for EoL management of solar waste. This phase involved desk-based research on identifying appropriate technology and approaches to develop local collection and treatment capacity.

The second phase of the SWAP Pilot was launched in May 2020 with an added contribution from the Doen Foundation. In this phase, the SWAP team looked to establish a pilot PV recycling facility with a PV waste processing capacity of 2.5 tonnes/day.

The funding [from our partners] will also support the capacity building of existing e-Waste dismantling companies in India to help them expand into the emerging PV recycling market. The project motivates local employment generation and contributes to establishing a formal solar waste treatment sector in India compared to the other waste stream sectors that are highly unorganized.

pv magazine: What were the pv panel recycling technology/process options before you?

Ankit Kapasi: Based on Phase I’s findings, we were investigating two different ideas to find a better fit for India. One was thermal decomposition, and the other was mechanical delamination involving crushing and separation.

During 2019, we visited several electronic waste recyclers in Italy who were also testing solar products for recycling, including a pilot PV recycling facility that used thermal decomposition.

Thermal decomposition did not work well in the Indian context for various reasons like high power consumption, unstable electricity supply and increased emissions. So, after discussions with Poseidon Solar, our technology partner for SWAP, we decided to go with the mechanical option.

During a study tour to the Netherlands and Italy, the Sofies team, along with Poseidon Solar, made a pitch [for the crushing and separation process] to various organizations, including the Doen Foundation. The Doen Foundation, later on, supported us a little further in actually implementing this pilot.

As of September 1 this year, we have a functional PV module recycling pilot plant at Gummidipoondi, Tamil Nadu. The plant is set up at Poseidon Solar, which is a pioneer in silicon recycling in India.

In the meantime, we spoke to various organizations that already had waste solar PV panels lying with them.

pv magazine: Is the pilot scalable to higher waste recycling requirements?

Ankit Kapasi: The plant has a capacity of 2.5 tonnes a day. By May 2022 or a little earlier, we aim to process 150-200 tonnes of PV panel waste. We are in discussions with a variety of organizations, and things look extremely positive. Given our financial constraints, the process is semi-automated. However, it can be fully automated and expanded in efficiency and capacity fairly quickly.

Basically, at this stage, we intend to propose an infrastructure for the country and show how it works and how much it costs. To that end, we are making witness shipment. So if 200 panels were loaded from Surat, we would have someone from our team witness how the panels are packed to ensure that there is no additional damage to the panels and that social aspects like health and safety are taken care of. The panel waste is shipped in a sealed/locked truck to avoid any pilferage. We are also creating a list of standard operating procedures (SOPs) for the industry to follow, should recycling becomes commercially viable.

The technical feasibility of the plant currently looks good. Talking about economic viability, transportation is a considerable cost, especially when panel waste is collected from other parts of India. So, if transportation costs are managed in the long term, we can have a much better financially viable business model. It still could mean that there might be a requirement for having added financial incentives.

Right now, pv recycling is a very gray area: There are doubts like whether it fits under the e-waste or will there be a separate regulation for it. In that sense, the idea here is to have a commercially, financially, and technically viable system, as well as SOPs, the right kind of stakeholders and all the processes in place for the country, should the government regulations come into effect.

Having said that, I still doubt whether people will be willing to send panel waste for recycling proactively.

pv magazine: How much waste have you collected for processing?

Ankit Kapasi: A Gujarat-based PV power plant owner, which had about 212 broken PV panels lying at their plant in Surat, was kind enough to give the solar panel waste to us at no cost. In comparison, other companies were asking for money in exchange for waste. And given that we are working within a project’s constraints, we didn’t have money to pay for the waste we collected. We could collect the waste and pay for transport, but we didn’t have the money to pay for the waste. We are still working through that challenge, but we have collected five tonnes of waste and are collecting more as we go on.

pv magazine: Collection and transportation from rooftop solar and other smaller installations would be an even more significant challenge than utility-scale projects. What are your plans for this segment?

Kishore Ganesan: India has installed about 36 GW of grid-connected solar capacity now, of which more than 90% is large utility-scale projects. So our process is initially targeted towards the utility-scale market. But for the rooftop and off-grid segment, we are trying to investigate the feasibility of mobile recycling units.

Ankit Kapasi: There are three components to our project. Component three is what we are doing with Signify and Doen Foundation, i.e., the actual solar PV recycling. Component two is the capacity building of existing e-waste dismantlers. Component one is where we have a struggle. It includes identifying and aggregating off-grid solar waste across the country, travelling to those rural pockets and running awareness campaigns, and reaching out to them for collecting as much data as possible. We have included this component as part of the wider proposal, but we don’t have the funds to deliver that yet.

Given that, we are not a big advocate of giving incentives, because if you start offering incentives to those who are holding waste, it will become an expectation. And that’s not sustainable in the long term.

Ideally, we’d like to invest either into having plants in other parts of India or, as Kishore said, mobile plants—the ones that can be moved around, especially for the smaller volume of waste from the rooftop and other installations.

pv magazine: How does the process work? And what is the material recovery rate?

Kishore Ganesan: Regarding the process itself, we don’t have something highly investment-oriented, as our pilot plant is repurposed with certain existing machines. So it’s easier for e-waste recyclers or existing solid waste recyclers to take in solar waste whenever they find it economically feasible.

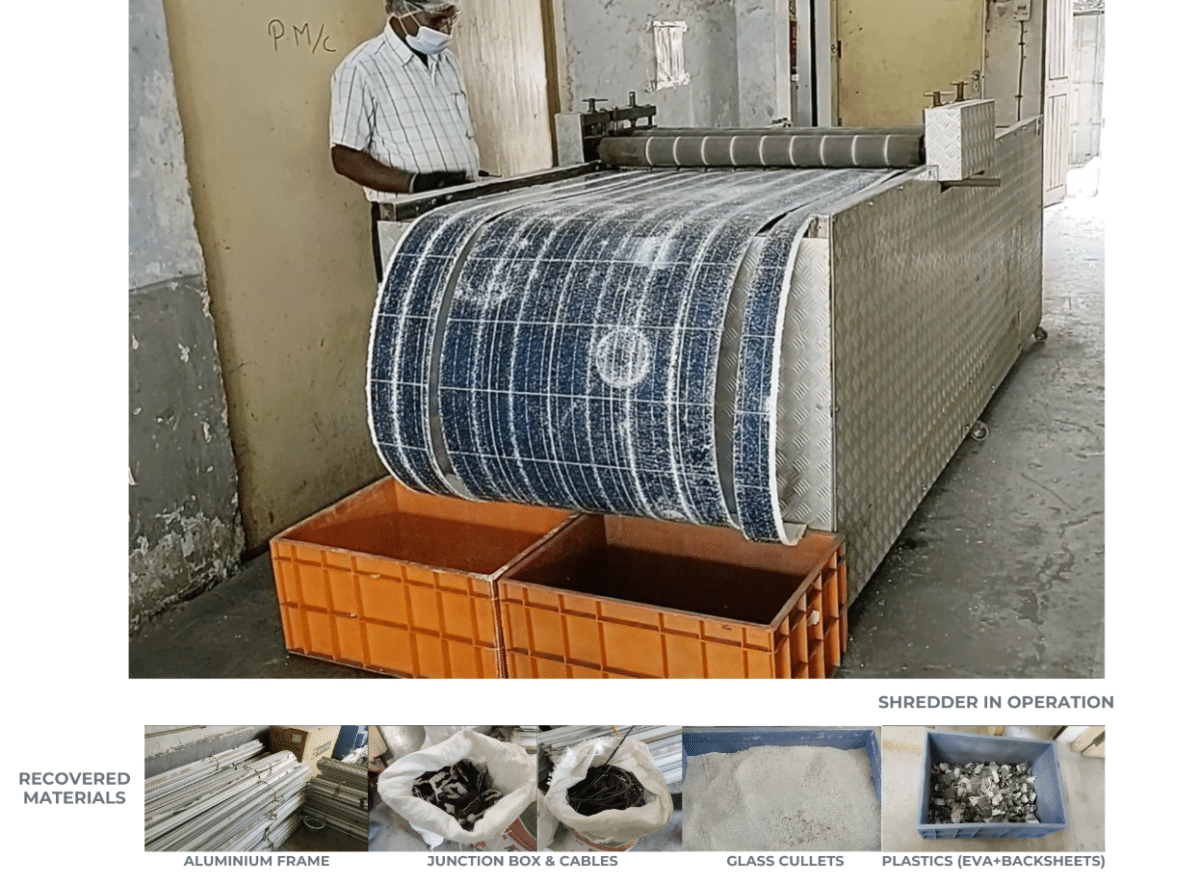

As soon as the panel comes in, we remove the junction box and the aluminum frame. The delamination process doesn’t involve any chemicals, it’s completely mechanical. We use techniques like sieving to separate the recovered materials. It can be replicated as well, and it is also eco-friendly in that sense.

For this plant, currently, we have around 60-80% material recovery rate. The reason I’m giving out a range is that the plant is still in a pilot stage. We recover aluminum, glass, plastics, and e-waste like the junction box and cables. So we still need to refine our process to recover solar cell materials like silicon and silver.

Ankit Kapasi: The efficiency [of our process] is fairly low, but it can increase. We will not stick to this one technology if it requires adapting a certain portion to improve efficiency. We want to come up with a final technology that is most suitable for India.

Kishore Ganesan: We are aiming to make our facility commercial-scale. Mechanical delamination is the process currently followed even in Europe. It’s a purely mechanical technique of separating glass and aluminum. Then, there are so many labs and pilot processes involving chemical delamination and thermal delamination. But that needs to be studied for scaling up and costs incurred.

pv magazine: How much amount of pv module waste is estimated to build up in India, especially considering the long life of pv modules?

Kishore Ganesan: The International Renewable Energy Agency estimates around 4.5-7.5 million tonnes of pv module waste by 2050 (0.05-0.325 million tonnes by the next decade). Given the quality concerns about the imported PV panels in existing installations and considering the possible scenario of re-powering PV power plants with new and efficient modules, it can be said with confidence that PV module waste will accelerate in the next ten years.

pv magazine: How much is the awareness about PV waste recycling within the Indian solar fraternity? Your message to the industry?

Kishore Ganesan: Currently, in India, we can see minimum awareness about PV waste recycling, given that the waste hasn’t piled up significantly. A project like SWAP can help proactively plan for tackling the PV waste problem that is undeniable in the near future. We are looking forward to partnering with organizations that are potential holders of PV waste. We can be reached at ankit.kapasi@sofiesgroup.com and kishore.ganesan@sofiesgroup.com

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

This attention to the “rear end” of PV Modules is indeed comnendable and must be supported by Solar Energy Organizations in India… to ensure this “green solution” doez not become a “grey/black Waste Problem”.

Once India wages “REAL WAR” against Pollution… and implements THE ZERO POLLURION POTION / SOLUTION…. about 500GW of Solar Panels Waste will need to be handled Annually or 30Million Tons/yr (16W/kg)… but one has 20-30 years to achieve…. Zero Waste (???) …. This start is phenomenal… now let the “seed” grtminate and grow….

Interesting thing appears the thousands of Govt PhD’s etc… donot appear to be…. ANYWHERE AROUND… SUPPORTING THEM MOVE ALONG…. AS A MINIMIM…???

.

Good jobs

Need the concerned person mobile no. Regarding recycling plant for purchase