From pv magazine 02/2021

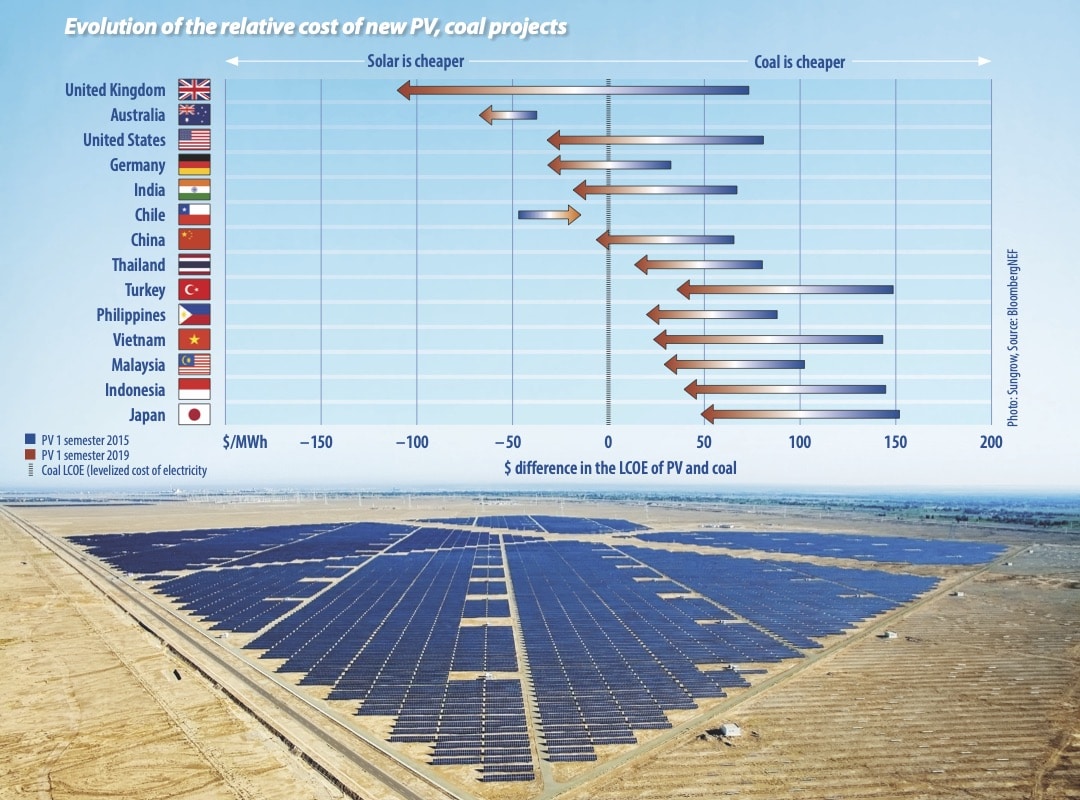

A report published by BloombergNEF’s Climate Finance Leadership Initiative in September 2019 states that: “New wind and solar have become more cost-competitive than coal in most of the world. Provided there is sufficient revenue certainty and policy stability, developers can now deliver lower-cost electricity using mainstream renewables than can coal-fired technologies.” The report, titled “Financing the Low-Carbon Future” depicts the cost of electricity generated from PV relative to the cost of coal, excluding the environmental externalities of coal.

For the two European countries plotted in the BloombergNEF graph, the lower levelized cost of electricity (LCOE) for solar compared to coal largely reflects the rising carbon price in those countries. However, for most of the other countries included, solar electricity prices are competitive without any carbon price. Yet according to the same graph, for Thailand, Turkey, Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia, Indonesia and Japan, coal remains cheaper than solar – a situation that is likely only to have improved since its publication.

Other Asian factors

Michael Grubb says that there are a number of factors in some Asian countries that may make coal investment more attractive than solar – despite the LCOE. Grubb is a professor of International Energy and Climate Change Policy at University College London (UCL), and a lead author in several reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which is the United Nations’ body for assessing the science related to climate change.

“Obviously if [the] LCOE is higher for solar that will substantially inhibit adoption – and reasons for this are important to consider … but many other factors can matter,” says Grubb. These factors can include countries not having adequate business and regulatory infrastructure to help smaller businesses develop and deliver PV and the associated supply chains. This capability gap is especially relevant when considering the corresponding technical capacity for installation and maintenance of PV systems, and the business requirements for mutual contractual certainty.

Another factor inhibiting PV adoption, notes Grubb, may be the terms of connection, such as the contractual model for the purchase of the PV electricity. Grubb adds that “credit-worthiness can be a concern, perhaps particularly for international investors who will factor in exchange rate risks.” Indeed, research carried out by the UCL team concluded that country risk is a major factor affecting the cost of capital for solar projects.

Asia’s coal pipeline

A report published in January by the Global Energy Monitor (GEM), a not-for-profit organization funded by the U.S.-based Ford Foundation, the German Institute for International Cooperation and the European Climate Fund, found that since 2014, the coal project pipeline of the world’s leading coal power nations has shrunk by around two-thirds. Of these countries, only South Africa is not in Asia.

It remains to be seen whether this trend will continue, however GEM’s report argues that the future will depend substantially on the availability of financing. Asia’s new coal-fired power investment is predominantly underpinned by export credit agency finance, argues the report, adding that this has started to dry up thanks to caution being displayed by primarily South Korean, Japanese and Chinese lenders.

Grubb argues additionally that while most of the coal plants being built in Asia are funded through government entities and financial institutions, most renewables projects attract private sector finance. Government financing, in this instance, may not be the smart money.

Some academic studies, Grubb continues, have found Southeast Asian coal generation projects were advanced by parties exhibiting outdated thinking and neither knew, nor had any reason to care about renewable energy or climate change. Therefore, institutional inertia is a factor that needs to be addressed if some developing Asian countries are to embrace the energy transition.

“Large, centralized utilities, which have developed based on the conventional model of building ever larger power plants, will often have their power and identity rooted in those technologies and systems,” says Grubb. “If a country’s electricity is run by big system engineers and is organized around financial and regulatory structures appropriate to billion-dollar investments, they are going to struggle with small-scale distributed energy sources like solar – which may also, to be blunt, undermine their political and financial power base.” Inertia and self-interest, in this instance it appears, can often be linked.

Cautious optimism

Apart from the institutional inertia that Grubb refers to, another main reason for caution is that often what appears to be positive development, may, on closer inspection, be full of loopholes.

In July 2020, for example, the Japanese government announced that it will tighten state-backed financing criteria for foreign coal-fired power plants. However, Japan’s decision includes exemptions such as when there are no alternatives to coal for the energy stability of a country and provides the investor with the opportunity to deploy so-called “clean coal” technology from Japan. Critics say that these exceptions demonstrate that Japan’s environment ministry has little influence on Japan’s powerful Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) – which has been a strong backer of coal generation exports.

Another recent announcement that requires caution is the one made by Pakistan’s prime minister in December; that the country will stop commissioning new coal plants. This is because existing projects under development will be built, while Pakistani coal will continue to be mined for liquid and gas fuels, in a process that results in very high levels of environmental pollution.

That said, the pushback against Chinese-financed coal plants in Pakistan appears promising. It shows that partners to China’s belt and road initiative (BRI) don’t have to take whatever China offers. Instead, they can negotiate for renewables – an increasingly important and fast-growing export. In fact, one week before the Pakistani coal announcement, the country’s energy minister met with the Chinese ambassador to discuss investment in renewable energy. The Chinese government has been criticized for continuing to invest in coal projects abroad even after announcing, in September 2020 that it will become carbon neutral by 2060. It has also added to its domestic coal generation pipeline. GEM has tracked an increase in China’s pipeline from 206 GW in 2019 to 254 GW in 2020. On the other hand, China’s PV installations increased to more than 48 GW in 2020 – a 60% increase on 2019.

China, says Grubb, finances “a lot of everything” and it is unclear whether the country’s leadership has arrived at a decision as to whether it favors coal over renewables. “Still, I’ll predict one thing: almost all those countries keen to host Chinese-funded coal plants will end up regretting it – so even might China.”

It’s the reforms, stupid

There is no doubt that more international pressure will be placed on China, Japan and South Korea to decrease or even cease coal investments abroad and bring their foreign activities in line with domestic action, since all three countries have set national net zero targets.

Moreover, U.S. President Joe Biden’s decision to rejoin the Paris Accord immediately on taking office last month, might provide a further boost to international climate change mitigation efforts.

What is very much needed is a step up in electricity market reforms in the emerging Asian economies. “The big centralized model worked well enough to support rapid expansion based on big power plants, but many governments are worried about the inefficiency of the model in a rapidly changing context,” argues Grubb.

“It’s easy to be simplistic – liberalization is not a panacea – but injecting some competition can be structurally very important and helps to open the system to new opportunities – like renewables.”

Similarly, Grubb continues, “it is easy for some government-led systems to become mired in cross-subsidies – just look at India, where a major hurdle for renewables at scale is the way agricultural electricity is almost free, and railways effectively cross-subsidize coal plants.

“So, the issue really is aligning power sector reform efforts to also take advantage of the opportunities now afforded by renewables. That is key for many countries.”

By Ilias Tsagas

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

The ONLY REASON one is moving to Cleaner Energy is…. TO SAVE HUMAN SUFFERING (275Million DALY) and PREMATURE DEATHS (~9MILLION) DUE TO POLLUTION…

If the “Cheapest Cost” is the Criteria… then just build Nuclear Plants…. WITHOUT ANY PUBLIC SAFETY FEATURES (Like Fossil burning vehicles, power plants etc…)… if there are nuclear accidents a million or so die…. so what Pollution already kills 9 Million… as we “twiddle our thumbs and counting the beans”… is it not???.. and dump the nuclear waste in the oceans… let marine life “glow in the dark” with radiation ……

Is this what use of Renewable Energy is all about…. to be the “cheapest source of Energy” so ALL CAN WALLOW IN (IN)CONSPICUOUS CONSUMPTION…. FOR TOMORROW WE HAVE TO DIE….🤔🤔🤔🤔…????

Articles whose basic premise is based on CHEAP SOLAR will NOT ELIMINATE POLLUTION…. Last 30-50 years are witness to this….

Use of Renewable Energy and rapid and sub/consequent shutting down of Polluting Facilities will… so these FOSSIL/NUCLEAR KILLING FIELDS RIP…..

THE EARLIER…. THE BETTER… I WOULD THINK…!!!

This finance based article compmetly ignores, knowingly or otherwise, that lowest cost is not the engine driving Tenewable and and Solar Power….. IT IS THE POLLUTION & ENVIRONMENT DEGRADATION, THAT KILLS AND MAKE PEOPLE SUFFER ALL OVER THE GLOBE…. the “Finance Industry” misses this completly as it focuses only on…. Zero Risk rather than Zero Pollution….

Yes…. “How many deaths will it take till he knows … that too many people have died…”… so very prophetic of the Financial Community… or… “When will they ever learn… when will they ever learn…”