On January 30, Solar Energy Corporation of India (SECI), issued a tender inviting developers to build 3 GW of solar power capacity with a condition that winning developers should create manufacturing facilities that can produce 1.5 GW of solar cells and panels domestically. In less than a week on February 5, Indian central government cabinet sanctioned US$ 1.2 billion for the second phase of the Central Public Sector Undertaking (CPSU) scheme through which state-owned firms, over the next four years, shall buy 12 GW of locally-made solar panels, to generate power for their own use.

India’s enthusiasm to promote domestic manufacturing is not totally new and was evident from the domestic content requirement clause mentioned in the Jawaharlal Nehru National Solar Mission. While working to achieve an ambitious target of 100 GW, if India is serious about establishing a cohesive manufacturing ecosystem for local production of solar modules, it should appropriately address the conundrum of “Should we catch up or lead?”

This article aims to shed light on the factors worthy to consider for manufacturing the manufacturing policy that is scalable, secure, strategical and supportive and promotes both growth and spread of solar while protecting the interests of manufacturers.

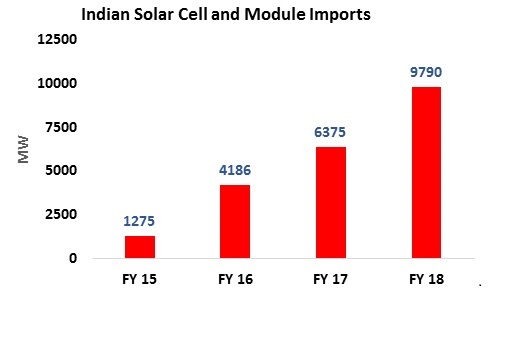

Source: DGTR Data, Ministry of Commerce

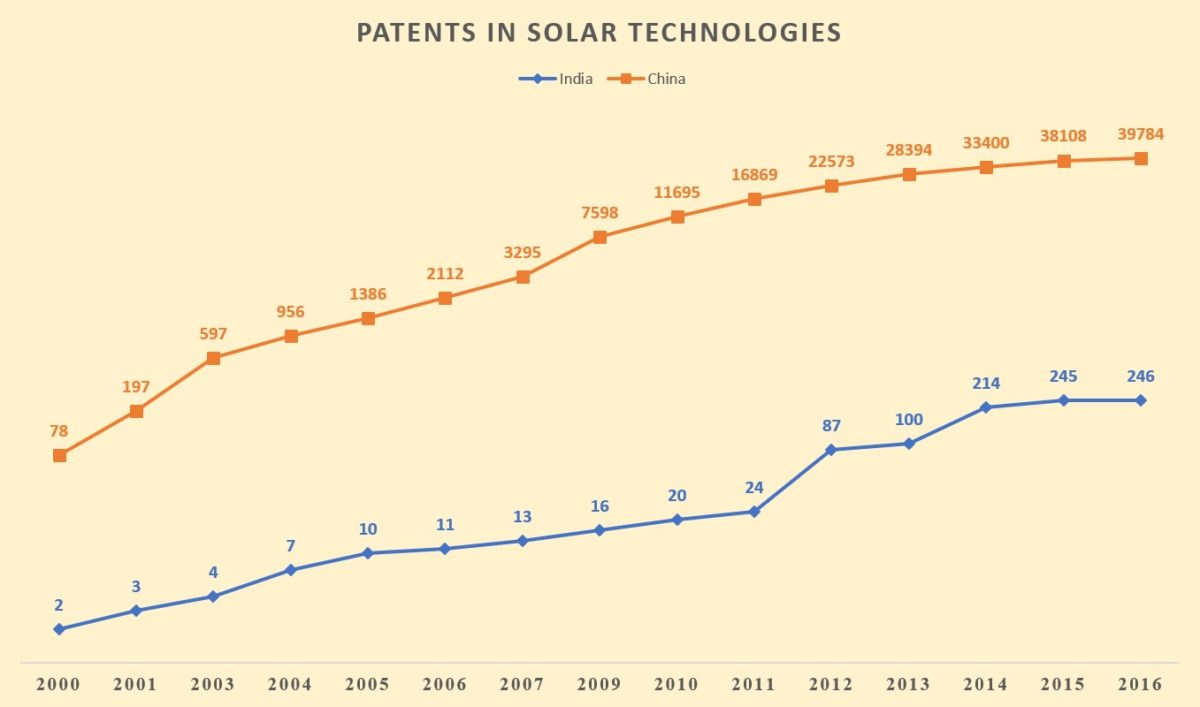

It is an indisputable fact that as of today, China is the global leader in solar manufacturing. Its dominance in this industry since 2007 can be largely credited to the incentives (more than 50 billion US$) provided to the industry by the government. These incentives made it the world’s largest solar manufacturing industry, one that became global price leader. As of early 2018, there were roughly two panels being made in China for every one being ordered by an overseas customer.

India’s aggressive target also bolstered use of Chinese modules, where in FY18 alone around 9.8 GW of solar modules were imported attributing to 85% of India’s demand.

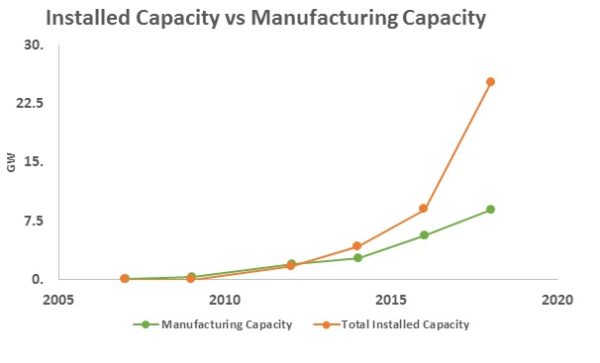

India’s installed solar capacity, thanks to the revised target, took a sharp rise since 2014, which however was not the case for manufacturing. Indian manufactures were unable to capture major chunk of the market share, owing to falling bidding prices by independent power producers (IPPs) and falling prices of Chinese modules.

Late last year, the Director General of Trade Remedies (DGTR)—formerly known as Directorate General for Safe Guards—imposed a 25% duty on foreign-made (developing countries) solar cells and modules. This safeguard imposition received mixed reactions from the industry.

The question however is “Is safeguard duty enough to safeguard the interests of manufacturers?” Or is it now necessary to look into the bigger picture of strengthening the policy support to make solar manufacturing in India appealing? The answer can be found through a “4S” approach to make a comprehensive and sustainable manufacturing policy.

Source: ISMA data on manufacturing and MNRE data on physical progress

Support (for supply chain)

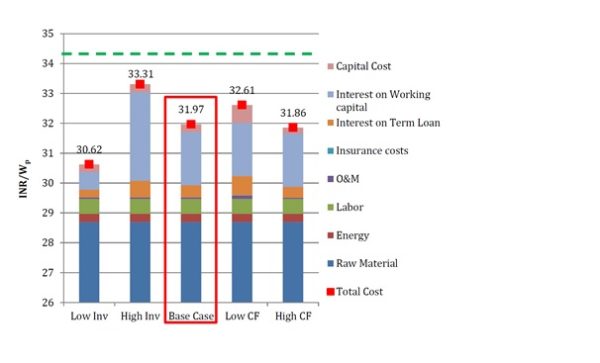

Indian module manufacturing is plagued currently by soon-to-be-outdated technology, over-dependence on raw material imports, limited access to cheap loans and factories often operating below their capacity. This results in domestic modules costing 10-20% higher than those imported from China, even after the safeguard duty is imposed.

“Interest subvention, a long-time pending request from Indian manufacturers, is a good step to begin with and can go a long way into addressing the woes of access to low-interest loans to Indian manufacturers,” says NSEFI Chairman Pranav Mehta.

“Along with this, there should be clear support from the government in terms of providing electricity at concessional rate,” adds Mehta.

Success of any manufacturing industry lies in the strength of supply chain, which is gravely missing in the Indian context. The government should consider initiatives aimed at supporting and reinforcing the supply chain to make manufacturing sustainable in India.

Source: State-level Policy Analysis for PV Module Manufacturing in India, CSTEP(2017)

Scale

China’s ability to make solar panels at about 20% less cost than Indian companies, simply turns out to be economies of scale. Larger factories can negotiate better contracts with suppliers and manufacturing equipment in these factories can efficiently match up the production rates at different stages in the process due to optimal utilization. This is an important aspect to be considered while developing the policy for solar manufacturing.

A country roadmap can be created by the government on the lines of Renewable Purchase Obligation (RPO) by establishing clear targets with timelines for manufacturing. An assured market demand for new manufacturers with pre-signed purchase agreements can help address the scalability of the market.

Security

Renewables, in Indian context, are often believed to alleviate India’s energy poverty while addressing energy security problem. While low prices of modules make a case for continuing import of solar panels, it doesn’t in any way contribute to India’s resolve for energy independence and security.

In June last year, to manage a deficit of $15.6 billion from its state sponsored renewable energy fund, China abruptly suspended the prevailing subsidies to its solar project developers. It is our duty to ensure that actions like these don’t impact the market development in India.

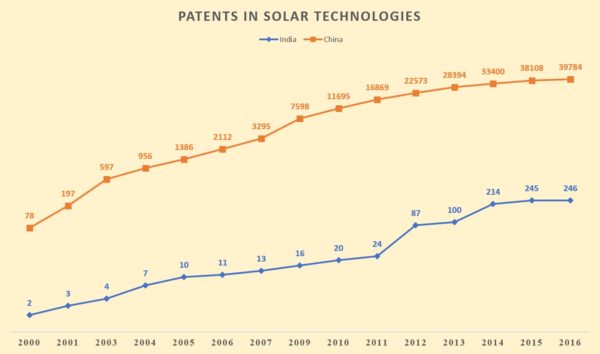

With targets of ‘100 GW by 2022’ and ‘40% of renewable in total energy generation by 2030’, India should find a way out from global solar mercantilism and achieve true energy independence. Aggressive R&D, innovative extraction techniques and facilities for mining and treatment of raw materials can be a good start to achieve this.

Strategy

While there is no doubt that India’s renewable targets will have appetite for modules, it is worth considering other strategic avenues where the domestically made modules can be consumed. India is the proud co-founder of International Solar Alliance (ISA), which comprises countries majorly from Africa, South America and the Pacific. These countries are developing nations with high hydrocarbon-deficit and large, untapped energy demand. Coincidentally many of these countries pay a higher tariff for energy consumption while they lack infrastructure and manufacturing capabilities.

Strengthening manufacturing capabilities in India will not only help achieve Indian targets but also strengthen the resolve of ISA by supplying modules to its member countries at affordable prices.

Many African countries like Senegaland Mozambique, countries in the middle east and former Soviet Union countries like Ukraine and Kazakhstan are already avid consumers of Indian modules at a smaller scale. Therefore India should not only focus on domestic consumption but also push for aggressive exports to developing countries.

NSEFI

Conclusion

While manufacturers in China enjoy a small advantage in labor costs, it has relatively little impact on prices and in the ever increasing globalized world, today’s regional price differences in making photovoltaic modules are not inherent and not driven by country-specific advantages. Technological innovations could rapidly level the playing field and therefore should be India’s primary target. Adequate support to R&D, targeting the entire supply chain, and creating and streamlining the process of availing incentives can go a long way in making India a global leader in manufacturing quality solar modules.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own, and do not necessarily reflect those held by pv magazine.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

1 comment

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.