A policy paper released by CUTS International highlights a critical challenge facing India’s secondary aluminium sector: escalating input costs that risk derailing the nation’s manufacturing ambitions, even as domestic aluminium demand is set to climb to 8.3 million tonnes by 2030, up from 5.3 million tonnes today.

The study comes at a pivotal juncture for India’s industrial growth, highlighting how the current import duty structure is inadvertently constraining MSMEs—the very enterprises that anchor the country’s manufacturing value chain and are indispensable to realising the vision of Viksit Bharat 2047.

Karnataka: Ground Zero for Industry Transformation

Karnataka plays an important and steadily growing role in India’s aluminium downstream landscape. While the state is not a major producer of primary aluminium, it hosts key refining and processing activity, most notably the alumina refining operations in Belagavi, and supports a diverse set of downstream industries across Bengaluru, Belagavi, Hubballi–Dharwad and other industrial clusters. Karnataka’s manufacturing ecosystem includes a wide base of MSMEs and engineering units engaged in aluminium casting, extrusion, machining, fabrication, die-making and component manufacturing.

However, this robust ecosystem now faces mounting pressure. Rising primary aluminium prices, influenced significantly by the existing 7.5% import duty, are squeezing MSMEs that depend on stable, competitively priced raw materials to remain viable. For secondary producers and fabricators operating on thin margins, even modest price fluctuations can determine survival or closure.

“The aluminium industry in Karnataka represents more than just production numbers—it’s about livelihoods, skill development, and regional economic stability,” noted a senior industry observer familiar with the state’s manufacturing landscape. “When MSMEs face cost pressures, the entire value chain feels the impact, from raw material suppliers to finished goods exporters.”

The Competitiveness Imperative

Navendu K. Bharadwaj of the Aluminum Secondary Manufacturers Association (ASMA) underscored the broader national implications: “Duty reduction of primary aluminum will enable downstream manufacturers to play a key role in driving demand for aluminum needed for development initiatives to achieve a Viksit Bharat in 2047. Aluminum value-added products are key components in sectors such as construction, infrastructure, automobiles, and electronics.”

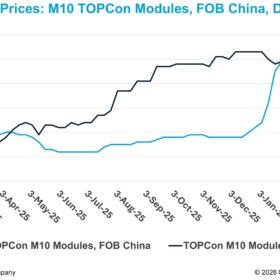

The policy paper reveals that the current duty structure keeps domestic aluminium prices elevated relative to international benchmarks, creating a competitive disadvantage for Indian manufacturers. This pricing gap particularly impacts sectors experiencing rapid growth—construction, renewable energy infrastructure, electric vehicles, and electronics—all of which require substantial aluminium inputs.

A Path Forward: Evidence-Based Policy Reform

The paper presents a compelling case for duty rationalisation, arguing that reducing import barriers would yield multiple strategic benefits:

· Strengthening downstream competitiveness: Lower input costs would enable India’s 3,500 aluminium MSMEs to compete effectively against duty-free finished imports under FTAs, expanding their market share in extrusions, castings, and fabricated products.

· Correcting inverted duty distortions: Eliminating the anomaly where raw aluminium faces 7.5% duty while finished products enter duty-free would restore fairness and incentivise domestic value addition over imports.

· Boosting employment and exports: Enhanced MSME competitiveness would create jobs in labor-intensive downstream sectors and position India to capture higher-value export markets, moving beyond bulk primary metal sales.

National Implications

As India positions itself as a global manufacturing hub under the Viksit Bharat 2047 vision, the aluminium sector’s health becomes a strategic priority. The material’s versatility—spanning construction, transportation, packaging, electrical applications, and emerging green technologies—makes it foundational to nearly every industrial growth story.

The policy paper concludes that rationalising aluminium duties represents not merely a sectoral adjustment but a strategic imperative for national industrial policy. By addressing cost structures that currently constrain MSMEs, policymakers can unleash the full potential of India’s aluminium value chain, driving employment, innovation, and economic growth across industrial clusters from Odisha to Gujarat, from Tamil Nadu to Maharashtra.