The solar energy sector, a cornerstone of India’s renewable energy ambitions, is facing turbulence as the cost of solar photovoltaic (PV) modules surges. Two recent developments—India’s imposition of anti-dumping duties on solar glass and China’s reduction in export rebates on solar modules—have escalated module prices, raising concerns about the viability and timelines of solar projects. These shifts underline the delicate balance between promoting local manufacturing, pursuing geopolitical strategies, and navigating the economic realities of global trade.

Indian clean energy firms will be required to use PV modules made from locally manufactured cells, sourced from a government-approved list of companies, starting in June 2026. This move aims to curb imports from China, India’s top supplier. While government projects already mandate the use of locally made PV modules from an approved list of domestic manufacturers, authorities have now extended this requirement to solar cells as well.

Anti-dumping duties and export curbs

In 2024, India initiated an anti-dumping probe into the alleged dumping of textured, tempered, coated, and uncoated glass from China and Vietnam to protect domestic manufacturers from unfair competition. This led to the imposition of anti-dumping duties—ranging from $565 to $677 per tonne—and a subsequent 10–12% rise in solar PV module prices, which constitute more than half of a solar project’s cost. Consequently, overall project costs have increased by 7–8%, putting numerous projects at risk of delay.

While the move aligns with India’s Atmanirbhar Bharat initiative to foster self-reliance, its timing is debatable. To meet its ambitious 2030 targets, which require adding at least 30–40 GW annually, India must accelerate project execution. Supply constraints have disrupted project schedules, threatening the country’s goal of achieving 500 GW of non-fossil power generation capacity by then. A phased approach—introducing duties only after strengthening domestic production—could have mitigated these disruptions.

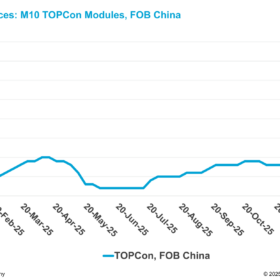

Adding to the challenge, China—which dominates the global solar supply chain—reduced export rebates on solar modules and ancillary components. Effective December 1, 2024, rebates on modules dropped from 13% to 9%, while those on aluminum frames and copper wires were eliminated. This policy change, aimed at curbing overcapacity and stabilising China’s solar manufacturing sector, has increased module prices by 2–4 cents per watt-peak. For Indian developers, this translates to a rise in electricity tariffs by 12–28 paise per unit, further straining project economics.

India’s dependence on Chinese imports remains a critical vulnerability. As of FY24, 80% of India’s solar cells and a significant portion of raw materials for modules are sourced from China. While domestic module production is ramping up, upstream components like wafers and polysilicon remain largely imported. Experts believe that this dependency will persist until 2027, when domestic capacities are expected to stabilise. Until India’s manufacturing capabilities meet domestic solar industry demand, restrictions on Chinese imports should be relaxed. The transition must be managed carefully, keeping project costs minimal and factoring in currency fluctuations, such as the depreciating rupee against the U.S. dollar.

Challenges in Power Purchase Agreements

While commercial and industrial (C&I) solar projects are growing in India, the closure of Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs) remains a challenge. Data from June 2024 on projects under the Solar Energy Corporation of India (SECI) indicates that large capacities of solar, wind, and hybrid projects have not been commissioned. A significant concern is projects where the effective PPA date has long passed.

Even assuming that projects with PPA dates in 2023 and 2024 will be commissioned soon, there is a backlog of over 12.5 GW of solar projects that remain uncommissioned. If prices are not controlled, these delays could lead to further instability. Foreign institutional investors are already withdrawing capital from the stock market due to a combination of global uncertainties and domestic economic concerns.

Balancing Domestic and Export Markets

Despite these challenges, there is an opportunity. Rising costs of Chinese exports could enhance India’s global competitiveness, positioning Indian manufacturers as reliable alternatives in markets like the U.S., where tariffs on Chinese imports have opened new avenues. Between FY2022 and FY2024, India’s PV module exports surged more than 23 times, reflecting the sector’s growing potential.

However, this export growth must be balanced with domestic demand. With India expected to achieve 132 GW of installed solar capacity by March 2026, the country’s projected module production capacity must increase accordingly. Small-scale projects, including rooftop solar installations, face delays due to the supply-demand gap. Sustained investments in domestic manufacturing—particularly for wafers and ingots—are crucial to achieving long-term self-sufficiency.

As domestic solar glass production scales up, prices are expected to stabilize. Policies like the Approved List of Models and Manufacturers (ALMM) and increased tariffs on imported modules have already spurred capacity expansion, suggesting a similar trend for solar glass. While rising costs and supply constraints pose immediate challenges, strategic investments in manufacturing and timely policy interventions can strengthen India’s position as a global solar leader. With innovation and foresight, India can overcome these hurdles and achieve its target of 500 GW of non-fossil power generation capacity by 2030.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own, and do not necessarily reflect those held by pv magazine.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.